Women in Science… do the numbers stack up?

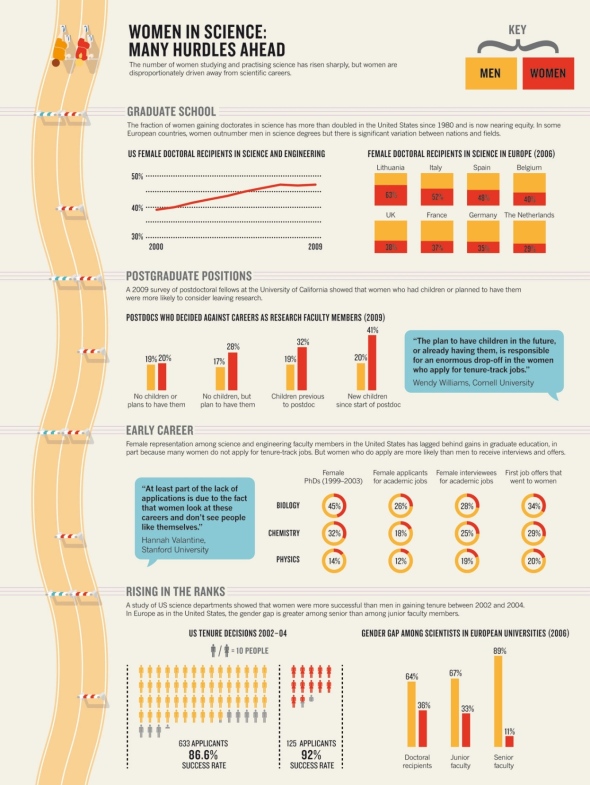

Posted: July 29, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Adelaide, Australia, career women, education, employment, employment opportunities, female scientist, gender bias, gender gap, misogyny, postgraduate, research funding, Science, science career, science communication, scientific literacy, South Australia, STEM, transition, University of Adelaide, women, women in science 1 CommentWith all the recent heated discussions about misogyny and gender bias spilling over from the Australian political sphere into broader debates about Australian culture, I was interested to see how the figures might stack up in the professional area of Science. I think this is an important line of enquiry when we have been discussing issues of Science literacy and the concept of Science equity in our Communicating Science course. Does this effect women in a particular way? Perhaps the opening up of Science needs to specifically target under-represented groups and does this include women?

Recent commentaries suggest it does. For decades, government reports and academic studies point to the deficit of women working in the field of Science and other STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics) areas; highlighting the negative impact this has upon the nation’s productivity through a shortage of key skills when only half the potential workforce is being utilised; particularly in the areas of engineering and technology. Some studies further identify a brain drain of Australian women professionals overseas although it would be interesting to know the statistics for gender ratios of incoming specialists – to what professional fields and how this contributes to a greater or lesser imbalance.

I was interested to learn, however, on the whole there is a healthy rate of girls enrolling in undergraduate STEM programmes, although with a clear bias toward allied health fields. Furthermore, women are also more likely to finish their undergraduate degrees than their male classmates. So what is the problem?

Statistics from Europe, the US and here in Australia suggest it is in moving on to postgraduate programs and/or transitioning into the workforce where most losses of female graduates occur. However, unlike other countries which have established major initiatives to retain and promote women in STEM, Australia has lost sight of both ‘equity and productivity agendas’ (DFEEST, p. 9).

For example only 22 women applied for Australian Laureate Fellowships last year and ignoring the two Laureate Fellowships reserved for women, only two of the 22 female applicants were successful. (Knowing how many men applied would also be good to know as it might suggest the female rate of 4 from 22 was pretty good). Perhaps more clear-cut is that women comprise only 12% of senior scientists at CSIRO and of the 20 newest Fellows elected to the Australian Academy of Science in 2013, none were women. (Gaensler, 2013). Statistics for Australian Laureate Fellowship recipients have improved somewhat this year with 4 out of 17 awarded to women. I’m not sure if there is anything significant in 3 of the 4 women recipients coming from the state of New South Wales… from where there was only one male recipient. The fourth national female recipient was our own Professor Tanya Monro from the University of Adelaide.

The report, ‘Female participation in STEM study and work in South Austtralia 2012’, published last year by Department of Further Education, Employment, Science and Technology (DFEEST) in South Australia covering a ‘learning-work continuum’ from 2008-2011, showed that only 22% of the engineering workforce were women and the unemployment rate for women engineers was almost twice as high as men. And of those female scientists and engineers surveyed in 2009-2012, 25% thought they would leave their professions within five years and close to 70% expected their career path to be ‘highly impacted’ by taking parental leave (p.9). Does this represent an ongoing and systemic cultural failure?

In an interview with ABC News, the head of the Federation of Australian Scientific and Technological Societies (FASTS), Anna-Maria Arabia, described how a scientist’s success is based on their publication rate, “But it is a publication rate that may have been calculated over the number of years that they have been in research since their PhD where perhaps five of those years may have been out of the workforce to raise children,” she said. [NB Since this interview was published, Anna-Maria Arabia has moved onto another position and FASTS has become Science & Technology Australia]

As a result of this structure many women simply give up trying to secure research funding (strongly informed by their publication rate) when they return to work as they can’t compete; instead turning to other roles such as teaching. In a feature interview below, Dr Heather Bray makes reference to the relevance of specific funding at the University of Adelaide established for women who have taken time out of their career to meet family responsibilities (as culturally women tend to be the family carers whether for children, spouses or elderly parents). It should also be noted that many universities are responding to the challenges of balancing a career and parenting through initiatives such as the establishment of on-campus creches and child care centres. But there is still an underlying belief held by many senior staff that a woman who is also a mother will not have the time nor energy required to fulfil research or senior academic positions.

Director of the ARC Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics at The University of Sydney, Bryan Gaensler, reflects that national funding agencies could do much better in this regard. He suggests that, ‘Rather than ask applicants to set out their track record but then essentially force them to apologise for their career interruptions, we need to let researchers play to their strengths. For example, applicants should be able to choose for each funding round whether they want their grant to be assessed mainly on past performance or on the quality of their proposed research program.’ (Gaensler, ‘Science needs more women’,The Australian, April 10, 2013)

http://www.nature.com/news/inequality-quantified-mind-the-gender-gap-1.12550# on the Nature website provides a clear and interactive illustration of the gender gap reflected in the employment rates and renumeration in science and engineering in US universities which you can play around with.

From the same online article, ‘Inequality quantified: Mind the gender gap’ (Shen 2013), the illustration below expresses international figures related to the presence of women in science at higher levels of research in academia.

This reflects a general condition of past progress having stalled in recent years, attributed to several factors including gender bias in recruitment, a lack of role models and women feeling they have to make a choice of commitment to career progression or parenting duties (whether existing or anticipated). The latter is interesting to consider as there is an inference women don’t see a career in research as compatible with having a family. While there is a focus upon women balancing a career with being a parent, it shouldn’t be overlooked that women are also more likely to be fulfilling other carers’ roles within their families. Nor should it be forgotten that young fathers are choosing (as well as being co-opted by working spouses) to take a more hands-on role in raising children while continuing to work full-time. I wonder how their careers are affected by this shift in roles? Does a more equal distribution of parenting duties result in two rather than one peron’s career being impacted? I suppose we are also seeing more men reversing the norm and choosing to forego their own career to take on the role of primary carer while their spouses develop theirs instead. It is in this circumstance or when women are single mothers that the disparity between pay for men and women comes into much sharper focus. This type of discrimination is unfathomable in our modern society and yet it is very real. Do we need to teach young women or even girls to demand better for themselves?

Claims that women are not as naturally suited to the study of Science or have less to offer than men used to explain the gender imbalance are strongly refuted by Bryan Gaensler. He reflects:

- First, there are robust studies that show that the performance of a research team improves when there is a larger proportion of women.

- Second, it is a terrible waste of the public funds spent on undergraduate education if we don’t expect most female students to actually use their training.

- Most crucially, some of the reasons why this imbalance exists are insidious, and need to be eliminated from the workplace.

Gaensler insists that above all, we need to accept that ‘gender neutral’ is not the same thing as ‘gender equitable’ (2013). This suggests adopting an approach which has a clear gender bias towards women rather than just trying to instill equal treatment. This is quite a controversial idea and many women insist that it is more important they are recognised on merit rather than because they are female. But it is also disturbingly real that as a result of subtle and not-so-subtle gender bias that women often have to significantly outperform their male counterparts to be recognised which is great for Science but not so good for women. Others are trying to expand the debate to look for more creative solutions than instituting direct but clumsy actions like quotas.

I think Gaensler has a point in view of extensive research demonstrating both men and women exhibit gender bias against women when recruiting or assessing funding applications without being conscious of it. The results of a relevant study I came across were discouraging. 127 professors of biology, chemistry and physics at 6 US universities were asked to evaluate the CVs of two fictitious college students for a job as a laboratory manager. The professors said they would offer ‘Jennifer’ US$3,730 less per year than ‘John’, even though the CVs were identical. They also expressed greater willingness to mentor ‘John’ than ‘Jennifer’. Microbiologist Jo Handelsman whose team was running the test said “If you extrapolate that to all the interactions that faculty have with students, it becomes very frightening,” (Shen, 2013). I agree.

But what are the personal experiences of real women of science locally and how do these inform their perspectives of the issues raised? In search of answers, I set forth with voice recorder and notepad in hand to speak individually with two women I have recently met through the Communicating Science course. As both are currently employed within the university sphere, their unique views are mostly focussed upon life in academia. I started by asking why they think we need somen in science…

[NB Following some trouble with the file sharing media, I have had to link to full tapings without post-editing. I apologise for the recording quality and hope to repackage cleaner recordings later. Please let me know if you are unable to access the audio files through the links to soundcloud]

1. Dr Natalie Wiiliamson, Play Interview… (15 minutes unedited)

First Year Coordinator, Chemistry (School of Chemistry and Physics), University of Adelaide, South Australia.

2. Dr Heather Bray, Play Interview… (40 minutes unedited)

Special Project Officer, School of Agriculture Food and Wine, and Senior Research Associate, School of History and Politics, University of Adelaide, South Australia.

A recent feature piece published in Nature (March, 2013) profiled several young and accomplished women scientists who were expecting their first child. Their outlook was positive and self-assured. They foresaw no difficulty in managing their responsibilities managing staff and research from maternity leave and returning to work as soon as possible. I say, ‘Good on them’ but I wonder whether they have a realistic view of the physical and emotional challenges motherhood entails. I think this balancing act mainly faced by women is very tricky to negotiate with a career. We have been brought up to believe we can do it all but perhaps we can’t do it all at once. Therefore, how careers for women in science can cope with absences without disadvantaging career promotion is something institutions and employers need to consider. While there is a clarion call for women to be valued as scientists, how can this be balanced with continuing to value their role as mothers in society? What was common amongst the profiles was the presence of strong female role models.

And so to end on a more positive note. The L’Oréal-UNESCO partnership was formed to focus attention on the gender gap in science not only by providing recognition and support to women researchers but to also highlight them as role models to younger girls and challenge gender stereotypes around the world. ‘By giving science a female face, the L’Oréal-UNESCO For Women in Science program strives to inspire today’s young women to become tomorrow’s researchers.’

This post has focussed upon an ongoing debate about a gender bias in Science and only briefly outlined some positive responses. A further exploration of the latter could well prove a worthwhile follow-up. And bear in mind that gender bias is not restricted to the field of Science. The gender gap is a product of our broader culture, affecting some more than others, and some not at all but which still needs to be addressed.

Thanks to Natalie and Heather for their contribution to this post as interview subjects.

DS.

Fine with a chance of rain…. getting the weather forecast right

Posted: July 29, 2013 Filed under: Day to Day Science, Uncategorized | Tags: Atmospheric sciences, Bureau of Meteorology, climate change, climate prediction, extreme weather events, heatwave, meteorologist, meteorology, patterns, poverty alleviation, risk management, sceptics, skeptics, Weather, weather forecasting Leave a commentIn a culture obsessed by weather we are constantly complaining – it’s too hot, it’s too cold, it’s too wet, or it’s too dry. Many suffer through winter waiting for summer and an equal number do the opposite while we identify favourite seasons and talk about being ‘summer people’ or ‘winter people’.

When we are all sweltering in the discomfort of a heatwave (and we certainly do that well in South Australia) we cling to the weather forecast looking for psychological comfort… just knowing there is a cool change on the way (even if somewhat distantly) brings instant relief. Recent online access to weather observations as they are occurring across the state and nation, allow us to spend an even greater amount of time and energy indulging in an almost religous meteorological fervour tracking the temperature, rainfall or stormfront but not really understanding a great deal about the ‘how’ and ‘why’.

Why do they get it wrong?

But woe betides those meteorologists when they get the forecast wrong. Bizarrely, we seem to hold weather presenters and meteorologists personally responsible when forecast weather conditions don’t materialise exactly as predicted yet the weather and climate are a mystery to most people. We place all our faith in the forecast but then take strange delight in smugly reflecting upon how wrong the Bureau of Meteorology got it yet again; even when only by a degree in temperature.

This points to our fickle obsession with weather and yet for many people there is little understanding of weather and climate conditions and how they occur. We constantly ask, ‘Why do they get it wrong?’ What we fail to appreciate is the weather forecast is purely a forecast [prediction or estimation] and due to the chaotic nature of the atmosphere, the massive computational power required to solve the equations that describe the atmosphere, error involved in measuring the initial conditions, and an incomplete understanding of atmospheric processes, forecasts become less accurate as the difference in time for which the forecast is being made increases.

We also fail to recognise the process of weather forecasting has improved immensely since it was first formalised in the mid to late 19th century, with greater collection of raw data, specialist knowledge and technological improvements. In response to widespread criticism about inaccurate forecasting, Dr Alan Thorpe (former head of the Met Office’s climate change arm), suggested the day-to-day broadcasts of local weather forecasts were too short and simple to properly explain anticipated weather conditions.

Informing and educating the public

Expanding the traditional format may better educate the public about how atmospheric conditions develop and influence the weather they experience. Perhaps this is part of the problem manifesting itself in a public resistance to an informed debate about the science of climate change in Australia. It is hard to meaningfully debate something you don’t understand. Here is a short overview presented by meteorologist Dr. Karl Braganza, of how weather and climate conditions are monitored and predictions are made by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology.

http://www.csiro.au/Outcomes/Climate/Understanding/State-of-the-Climate-2012.aspx

It is ironic that as our abilities to predict weather and climate improve, the weather is itself becoming less predictable with an increasing number of extreme weather events around the world attributed to long-term climate change. The video below provides an engaging explanation of the global climate system and links between recent extreme weather events. (Duration: 20 minutes)

‘Extreme Weather’, An episode of Catalyst, ABC Televison 2013

Planning for natural disasters

As well as informing our everyday decisions about whether (no pun intended) to wear a rain coat or cancel the school swimming carnival, being able to accurately predict the weather also underpins the effectiveness of service providers such as utility companies. For example knowing there is going to be an extended period of very hot weather enables them to manage day-to-day peak power supplies to homes over hot summers. And being able to predict short to long-term climate conditions has relevance for major infrastructure planning including strategic plans for state and nation-wide water supply as well as budget implications.

Weather forecasting is also crucial for mitigating the impact of extreme weather events. Just consider that climate and water-related hazards account for 90% of all natural disasters. Climate change scientists predict it will be developing nations which will face a greater number of extreme weather events in the future and yet they will be less equipped to either pre-empt or respond to these.

Professor Peter Webster of the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at the Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, attributes the disparity between the human impact of Cyclone Sandy (which hit the east coast of the US) in 2012 and those which hit developing nations, to planning which was made possible through accurate long-range weather forecasts (Webster, 2013). The difference is thousands of lives.

It is astonishing to consider that according to Webster, ‘while only 5% of tropical cyclones occur in the north Indian Ocean they account for 95% of such causalities worldwide’ (p. 17). They also have much less resilience and succeeding seasons of unpredictable weather conditions create ever-deepening impoverishment. The unpredictability of weather systems through climate change have undermined traditional weather forecasting knowledge and practices developed over hundreds of years leaving small-holder subsistence farmers at the ‘mercy of the heavens’. The spread of new technologies in poorer isolated districts can provide forewarning if an information-sharing network is in place but access remains patchy. (Herro 2011)

Webster cites the example of a pilot study demonstrating the advantages of timely forecasting in Bangladesh whose low-lying regions are regularly inundated by seasonal flooding. The UN estimated that weather warnings communicated to the community leaders of pilot areas ten days in advance of the 2007 and 2008 floods, allowed residents to harvest crops, lead cattle to safety and store water, food and personal belongings saved an average of US$400-500 dollars per household which is the average yearly income.

https://domesticsciences.wordpress.com/the-bits-that-didnt-fit/excerpt-from-p…climate-change/

‘The science is well ahead of our ability to implement it’

It seems a lack of resources is not only affecting meteorological offices in developing nations. Chief Scientist at the UK Met Office, Dr Julia Slingo suggested a lack of computing power (through supercomputers) due to limited funding was their biggest obstacle to creating better, hazard-relevant weather forecasts. In the journal Nature, she claimed, ‘The science is well ahead of our ability to implement it’, (Jones 2010). And so raw data is not the problem – the ability to analyse enough of it to ensure greater a greater degree of accuracy and certainty is, such as with Russia’s record drought which had a major impact upon global food security as the failure of Russian grain crops saw commodity prices soar.

Dr Slingo’s prayers have recently been answered with the UK Treasury committing to the purchase of a new supercomputer so the UK Met Office can develop ‘its world-class research base.’ Others suggest, however, even with all the computing power in the world someone still has to choose the best mathematical model and parameters for the computer to use in any given situation.

Some commentators go on to express a belief that climate science has become ‘state science’ pursuing a particular propagandist climate change agenda as opposed to a disinterested pursuit of knowledge. Hence they accuse such institutions as the UK Met Office as being committed to the wrong computer model and failing to update their climate assumptions; thus incapable of providing accurate weather forecasts and climate predictions. They use the past winter and current summer as clear evidence. [This alternative view published in The Spectator magazine can be read in full online. Similar commentary about the claimed 20% revision down of previous climate warming predictions by the UK Met Office can be found online at the home of the think-tank GWPF (Global Warming Policy Foundation); anthropogenic climate warming skeptics.]

Further Information:

The following video (another from ABC Television’s science programme Catalyst) entertainingly looks at the last 100 years of Australia’s recorded weather to find out whether it has really changed. (First aired November 15, 2012) Catalyst: Taking Our Temperature – ABC TV Science.

All in the mind …. the placebo effect (2/3)

Posted: July 25, 2013 Filed under: Health, Research, Uncategorized | Tags: alternative medicine, alternative therapies, Classical conditioning, double-blind testing, endorphins, health care, medical intervention, Nocebo, Placebo, positive thinking, Randomized controlled trial, sceptics, skeptics, wellbeing 1 CommentIn a previous post on July 16, 2013, ‘All in the mind… the placebo effect’ I described the concept and origins of placebos and the placebo effect. This post shifts focus to the changing perception of placebos within the field of scientific research and clinical practice using published articles framed by counter arguments. The literature largely signals a growing interest in the use of placebos – not because researchers believe placebos have the power to trick the mind into healing the body but because there is an increasing body of research providing evidence linking chemical reactions in the brain to development of our expectations which moderate and influence our behaviour and perceptions. (Scott et al 2007)

[I have included a couple of short videos which entertainingly explore the placebo effect…. and so if you aren’t in the mood for reading, or short of time scroll straight down to the visual aids. Alternatively if you are in the mood for some interactive experience watch the video at the end and follow the accompanying link to test one person’s idea of the placebo effect through an app. I am by no means recommending the app as I have not tested it myself being still rather old fashioned when it comes to phones but it could be fun – and by all means let me know. ]

And now back to the topic at hand….

Placebos have been critical in the running of randomized clinical trials as a comparison marker. As Kaptchuk writes in The Lancet (1998), ‘Until the RCT, medical therapy became legitimate because of beneficial outcomes; after the RCT, a medical intervention was only scientifically acceptable if it was superior to placebo… method became more important than outcome’, (p. 1724). Critics also recommend that a third ‘no treatment’ control group is used to gauge the placebo effect.

In some cases, it has also been shown that well-established prescribed medical interventions are no more effective than a placebo (or perhaps I should say the placebo is no less effective) suggesting that the effectiveness of the branded product is probably only due to the placebo effect. This seems quite profound when considering our increasing consumption of drugs and ballooning expenditure in the over-burdened health system. To read of widely prescribed anti-depressants such as Prozac testing no better than a placebo seems shocking. And this is not to suggest the anti-depressants in question are just ‘sugar pills’ – just their ingredients are not active for that specific illness. A survey of General Practitioners in the US revealed that 50% regularly prescribed ‘placebos’. This raises another concern regarding the possible side effects of non-active medical inventions (whether a drug or procedure) with other active ingredients upon people’s health which could be avoided.

So how can any non-active treatment seemingly be so effective?

‘The scientific study of the placebo and nocebo effect is part of the exciting advances in modern neuroscience on the way in which the brain normally controls many bodily functions. We do know that this is mostly done by operating below conscious awareness’, writes Marcello Costa, Professor of Neurophysiology, Department of Physiology at Flinders University.

(http://theconversation.com/mind-over-matter-the-ethics-of-using-the-placebo-effect-3752)

Animation: ‘The Strange Powers of the Placebo Effect’ from The Professor Funk.

The body of current research points to several factors underlying the placebo effect which are only now being unravelled through more extensive research and the use of such tools as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans to understand how the brain reacts to medical intervention. Between accumulated research findings and new MRI brain scans taken during testing as proof, it appears the ‘effectiveness’ of placebos which induce a sense of increasing wellbeing and also alleviate specific types of symptoms is linked to the opioid system. Researchers have found that placebo effects can stimulate real physiological responses, from changes in heart rate and blood pressure to chemical activity in the brain, in cases involving pain, depression, anxiety, fatigue, and even some symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. From research in the late 1970s we have known the placebo effect is linked to the release of endorphins which are the brain’s ‘natural pain relievers’ when it was shown that blocking the release of endorphins removed the placebo effect (Feinberg 2013). We can be conditioned to release such chemical substances as endorphins, catecholamines, cortisol, and adrenaline. Telling research participants they will likely experience adverse effects from the placebo treatment also reliably leads to them reporting those same symptoms – this is called the nocebo effect.

Challengers to alternative medicine practitioners and those who believe it is purely a case of ‘positive thinking’ propose the placebo effect can be largely attributed to a mix of the following mechanisms;

- Natural history where illnesses naturally peak and then taper off with recovery – patients usually seek medical treatment at the peak and so recovery correlates with treatment;

- Regression to the mean (natural fluctuations in illnesses);

- Standard medical and nursing care;

- Impact of modified rest, diet, exercise and relaxation;

- Reduction of anxiety by receiving a diagnosis and prescribed treatment;

- Influence of the doctor-patient relationship (including the desire by trial participants to ‘give the right answer’);

- Expectation of recovery; and

- Classic conditioning (which on a very basic level refers to our learned belief associating medical intervention with recovery but can also be more complex).

It is, however, difficult to unravel and measure these often inter-dependent mechanisms, especially when their significance will naturally vary from patient to patient. (McCann et al 1992)

Studies have also found the placebo effect is influenced by the manner of the placebo delivery and these variables needs to be accounted for in trial results. It has been shown in the last decade that variables such as the form of placebo delivery (pill versus injection, or pill colour or size); demeanour of the placebo provider (level of verbal interaction, body language, perceived level of ‘care’,etc); framing of the procedure; aims and expectations to participants; physical environment (hospital versus standard room); and there are now even claims that individuals will be variously disposed towards the placebo effect dependent upon their genetic make-up (Furmark 2008). There is also a recognised predisposition of participants to try to please with their responses which may skew results. Hence the push for a double-blind testing approach in trials to measure these influences.

Dean Leyson’s : The Placebo Effect (BTW if you can’t pick his accent, it’s Belgian)

Here is a list of placebo influencing factors:

- trusted brand-name drugs work better than others;

- expensive treatments work better than cheaper ones;

- green pills may be better for phobias and anxiety;

- red and yellow pills may work better for depression;

- sham devices may work better for pain than pills;

- treatments work better if administered by a practitioner perceived as being kind, warm and caring; and

- in general, invasive treatments (eg. surgery, injections, procedures) seem to work better than less invasive ones.

The sense of recovery and healing people credit to alternative therapies is also attributed by sceptics to a placebo effect. For example a study undertaken by Harvard Medical School researchers demonstrated that of the participants suffering from Irritable Bowel Syndrome those who experienced the greatest alleviation of discomfort had who received the most attention and care in the form of pretend acupuncture and non-active medication. All participants received fake treatment but were either given a minimal or high level of attention and interaction from those administering the treatments.

Numerous studies have demonstrated the placebo effect can be a significant factor in people’s sense of recovery – even if this is subjective on the part of the patient rather than an objective reduction in illness. This is why a growing number of researchers and medical practitioners believe placebos should no longer be wholly defined by their inert content/ attribute. Focus should be shifted to what the, ‘placebo intervention – consisting of a simulated treatment and the surrounding clinical context – is actually doing to the patient. Accumulated evidence suggests that the placebo effect is a genuine psychobiological event attributable to the overall therapeutic context,’ (Finniss et al 2010, p. 686). Thinking about this and the evidence of the placebo effect for pain relief, I wondered whether there was a role for the placebo in palliative care where it would perhaps raise less ethical issues. Something I will discuss in my final post on the placebo effect… to come.

In a US study involving asthma sufferers, it was shown the placebo had little effect on the measurable physical outcome of lung function (equal to the ‘no treatment’ control group) measured through lung capacity testing; versus the administration of a standard albuterol bronchodilator. However, the participants themselves reported improvements in terms of relieving discomfort and self-described asthma symptoms equal to albuterol. This supports the theory a ‘subjective’ placebo effect exists and that a placebo treatment may be just as effective as active medication in improving patient-centred outcomes. ‘It’s clear that for the patient, the ritual of treatment can be very powerful,’ notes Kaptchuk. ‘This study suggests that in addition to active therapies for fixing diseases, the idea of receiving care is a critical component of what patients value in health care. In a climate of patient dissatisfaction, this may be an important lesson.‘

Here’s how to administer your own placebo effect…. but at your own risk…

Website: Placebo Effect – A Beginner’s Guide http://www.placeboeffect.com/placebo-effect/

[NB having read the webpage and various blog posts of the app’s creator I have to say I don’t endorse much of what is written… a little too much ‘feel good’ content which in my opinion doesn’t accurately reflect scientific research despite using it to support their advocacy of the placebo effect… and business idea]

And here’s your very last little pill … There is also a published study (Furmark 2008) which claims to have found a certain variation of a gene linked to the release of dopamine which makes the individual far more susceptible to the sham treatment and therefore also the placebo effect. The ability to screen prospective trial participants based upon a lower susceptibility to the placebo effect is argued for on the basis of creating more efficient medical trials, reducing the time and costs of testing and therefore getting effective treatments onto the market faster and more cheaply to benefit patients.

Some recommended further reading:

http://theconversation.com/not-just-smoke-and-mirrors-placebos-place-in-modern-medicine-4587

A third and final post will discuss contrary views and ethical considerations attached to the administration of placebos. Did you know placebos are still regularly ‘prescribed’ by GPs here and overseas?

Until next time,

the domestic scientist.

A Fatal Attraction to Fungi in 8 Graphics

Posted: July 18, 2013 Filed under: Disease, Research, Uncategorized | Tags: active ingredient, Beauveria bassiana, bio-pesticides, biopesticide, death, fatal attraction, fungi, fungus, hygiene, infectious disease, insecticide, Malaria, malarial research, mosquitoes, pesticide, preventative measures, Research, resistance, vaccination, y-tube olfactometer Leave a commentAs a Thursday night post I’ve decided to share my mini class presentation with you. How lucky are you?! (But ‘lady luck’ could be a whole other blog post topic…)’

As part of the assessment for our ‘Communicating with Science’ course we were required to mentally digest and communicate the contents of a peer-reviewed scientific journal article in a 2 minute timeslot followed by a brief Q & A with our classmates and a couple of obliging ring-ins. It was a very useful and practical exercise pin-pointing what the most significant and interesting aspects of the paper were with a view to being able to then communicate the information clearly and accurately… and of course, engagingly. With another assignment due the previous night preparation time was limited…

I opted for a 2013 paper I had already read for my blog post, ‘Why might stinky feet be so important in the fight against malaria?’ but had only briefly referenced. This is a tale of fatal attraction and I hoped its quirkiness might appeal to the audience comprised of my classmates (and assessors) as it had to me.

The Paper…

The paper detailed experiments focussing upon fungus as an active ingredient in a biopesticide control of malaria mosquitoes. I love it when the natural world has the answers, and especially when those solutions can trump our own ‘inventions’ and their associated adverse side effects. And so the concept of biopesticides (with a likelihood of less harmful side effects) seems really cool to me.

The Presentation…

Slide 1.

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease. It begins with a bite from an infected female mosquito, which introduces the microorganisms through saliva into the circulatory system from where they travel to the liver to mature and reproduce.

A mounting problem with preventative measures for controlling malaria is that mosquitoes are becoming resistant to some chemical insecticides and so some researchers are looking at alternative biopesticides (‘a form of pesticide based on micro-organisms or natural products’).

(Click on slide for enlarged image)

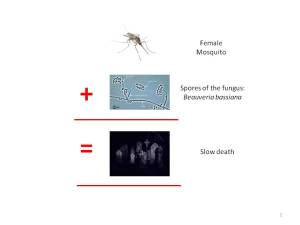

Slide 2.

In this case the active ingredient under research is a fungus called Beauveria bassiana which infects insects and kills them slowly (in relative terms for insects… 1-2 weeks for mosquitoes).

(Click on slide for enlarged image)

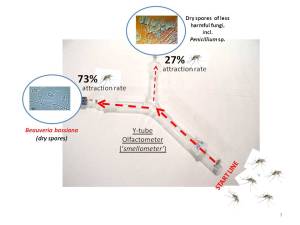

Slide 3.

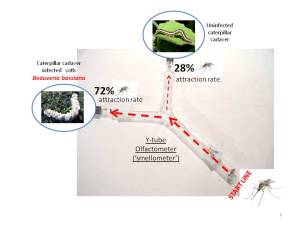

Previous research has shown insects may be deterred from landing upon pesticides which are harmful to them. If the fungus proved a deterrant to its target than it would not be an effective active ingredient in a biopesticide. Hence, the researchers wanted to see if mosquitoes would be repelled by the Beauveria bassiana. They did this by giving a ‘cage’ of mosquitoes a choice between two fungi using a y-tube olfactometer (I like to call it a ‘smellometer’). And to the researchers’ collective delight, the mosquitoes chose Beauvaria (despite its fatal effects) over the less harmful and obviously less sweeter smelling Penicillium. This suggested the Beauveria bassiana smells almost irresistible to female mosquitoes. That would seem to suggest the researchers had been successful in reaching the objective of their experiments… but they wanted to go further. They knew mosquitoes would almost definitely become infected by landing upon a surface to which dry fungi spores had been applied (tests showed a 95% likelihood) but this would likely prove a very onerous, time intensive and expensive task – especially when considering the extent of land where malaria is present. And so the researchers also looked to prove that Beauveria bassiana is irresistible to female mosquitoes through ‘natural’ transfer.

(Click on slide for enlarged image)

Slide 4.

In this case, the fungus takes advantage of the mosquitoes somewhat gruesome predilection for feeding upon insect larvae, dead or alive. And mosquitoes are particularly partial to the squishy, tender bodies of caterpillars…

(Click on slide for enlarged image)

Slide 5.

… which may already be infected by Beauveria bassiana and dying a slow death. The researchers tested a hypothesis that female mosquitoes would be drawn to infected caterpillars over infection free caterpillars. (Click on slide for enlarged image)

Slide 6.

The earlier test was repeated but with cadavers of caterpillars infected with Beauvaria bassiana against caterpillar cadavers which weren’t infected. Similar results were achieved.

(Click on slide for enlarged image)

Slide 7.

While this proves that Beauveria bassiana could be a very useful active ingredient in bio-pesticides to prevent malaria, the researchers couldn’t fully explain the fatal attraction the fungus had for the female mosquitoes. These are also experiments at the early stage of developing a biopesticide. Conclusion: More research needs to be undertaken.

(Click on slide for enlarged image)

Slide 8.

Interestingly, research has also shown, the slow death by biopesticides (in comparison to the rapid death caused by insecticides) also makes it harder for the mosquito population to build up a resistance. Isn’t that cool considering the ability of mosquitoes to build up resistance to traditional pesticides has been affecting the ability to control mosquito populations recently? Win-win, I say.

(Click on slide for enlarged image)

In case, you’re wondering – Yes it did run over the allocated two minutes…. do you know how fast two minute speeds by? Feedback suggested I could have left out slides 4, 5 & 6 and just covered the key investigation of the experiment.

Interesting questions I fielded from the audience included among others: whether application costs of biopesticides were affordable and would this affect its viability ergo was cost a factor between traditional pesticides and biopesticides; and could mosquitoes infect eachother… do they feed on eachother as they do on other insects? Do any readers know the answers?

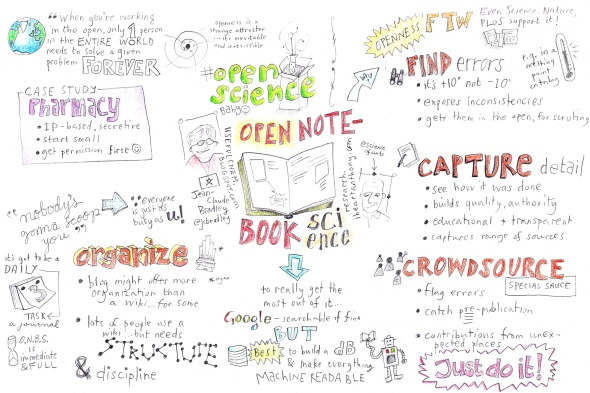

Science Literacy – couldn’t be more topical.

Posted: July 17, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a commentJust released from: Australian Academy of Science, an Australian Survey of Science Literacy.

Excerpt: The greatest fall in knowledge of how long the earth takes to orbit the sun is amongst younger cohorts.

- Q: How long does it take for the Earth to go around the Sun? (Percentage by group, 2013 and 2010)

For the full report:http://www.science.org.au/reports/documents/ScienceLiteracyReport.pdf

All in the mind…. the placebo effect

Posted: July 16, 2013 Filed under: Health, Research, Uncategorized | Tags: active drugs, active placebo, alternative medicine, inert substance, medication, mind over matter, opoid, Placebo, placebo effect, Randomized controlled trial, sceptics, Sham surgery, skeptics Leave a commentPlacebo – Drug of Champions?

Could infamous cycling champion, Lance Armstrong, have done so well if his ‘drug of choice’ had been a placebo? I pose the question because it may not be as ludicrous as it sounds according to research by Italian neuroscientist Dr Fabrizio Benedetti. Although with hindsight, believing Armstrong was so successful without assistance seems just as ludicrous.

Most people have probably heard of ‘the placebo effect’. This is a term I seem to be hearing with more regularity and recently I have begun to wonder if it has become just another fashionable, catchy saying; likely misunderstood and misapplied but used nevertheless because it sounds edgy and knowledgeable.

There also seems to have been a cultural change in attitude towards the framing of placebos. This may be due in large part to increasing distrust of prescription medications and the appeal of the idea of non-intrusive healing through ‘positive thinking’ or of ‘mind over matter’; especially when the terminally ill and their loved ones are desperately looking for a cure where conventional treatments no longer give any hope. Guess et al (2002) also note a shift in the bio-medical research field and among medical practitioners, describing the placebo as, ‘transformed in a few short years from a sham in medical practice and a control agent in clinical trials to a therapeutic ally’, (p.1).

To most lay people I think ‘the placebo effect’ is commonly understood in reference to patients taking a ‘pretend medication’ (placebo) but when believing it to be real attest to a physical response to the ‘medication’ – which may be either positive or adverse. This is how I would have explained the placebo effect if asked but I was by no means sure I understood the phrase properly either. Are people really misinformed when they think the placebo effect points to an ability of the mind to enhance the body’s ability to overcome physical ills? It is certainly an appealing concept and one which can seem more reasonable when we are forever being told how little we truly understand the workings (or unmapped potential) of the human brain.

And so sensing I was on shaky ground in my own understanding of the placebo effect I decided to make it the topic of a couple of blog-posts and I discovered there are a number of interesting perspectives to discuss.

So here goes…. a brief history on the origins of the placebo…. (and its effect).

The term ‘placebo’ comes from the Latin verb ‘placare’ which means ‘to please’ (as opposed to ‘nocebo’ which means ‘to harm’). Although ‘placebo’ started to be used in English during the 13th century, it wasn’t part of medical terminology until the late 18th century. A medical dictionary from 1811 defined the term as ‘any medicine adapted more to please than benefit the patient’ which reflects the practice of doctors of the time to give some patients placebos in the form of bread or starch pills because they had little confidence in the efficacy of their ‘real’ range of medications. Doctors would also prescribe ‘sub therapeutic doses’ of ‘pharmacologically active drugs’ (Edward 2005, p.1023) in order to satisfy those patients who were simply looking for the process of treatment and possibly to protect their authoritative standing.

Generally, a placebo is an inert substance with no inherent pharmacological activity, and looking, smelling and tasting like the real drug being used. An ‘active placebo’ may be used which is one possessing its own inherent effects but which don’t apply to the condition for which it is being prescribed. A placebo may also be a procedure rather than drugs or medication. This can be quite extreme extending to placebo surgery where a patient is anaesthetised and ‘superficial procedures’ including skin incision are performed without surgery being undertaken (Rajagopal 2006). I have been wondering if the previously mentioned ‘placebo surgery’ is a treatment or a component of clinical trials. Either use is somewhat hard to fathom and points to much of the current debate surrounding the ethics of using placebos through deception, although technically participants in clinical trials must be made aware that they may receive a placebo rather than the active drug or real procedure.

The phrase ‘the placebo effect’ has been attributed to American anaesthetist Henry K. Beecher in his work, ‘the powerful placebo’ (1955), when he reported that, on average, a third of his patients with a range of medical complaints improved when taking placebos. Rajagopal (2006) claims this then led to the use of placebos in the establishment of randomized control trials (RCT) where ‘active drugs’ are tested against placebos rather than no treatment which Edwards (2005) suggests, ‘implicitly assumes that the placebo itself exerts an effect’ although not of a pharmacological nature (p.1023).

In the next blog-post I will identify current opposing (as well as overlapping) views of researchers about the application of placebos, including a case study, and return to make sense of the question first posed by this post: Could Lance Armstrong have done so well if his ‘drug of choice’ had been a placebo?

References:

Edwards, M 2005, ‘Placebo’, The Lancet, vol. 365, pp 1023.

Guess, HA, Kleinman, A, Kusek, JW, Engel, LW 2002, The Science of the Placebo, BMJ Books, London.

Rajagopal, S 2006, ‘The placebo effect’, The Psychiatrist, vol. 30, pp 185-188.

Why might stinky feet be so important in the fight against malaria?

Posted: July 14, 2013 Filed under: Disease, Health, Research | Tags: Anopheles gambiae, anti-malarial drugs, attraction, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, early diagnosis, infectious disease, Malaria, Mosquito, odour, pathogens, poverty, Research, smell, transmission Leave a commentNot so long ago while flicking channels as is my usual bad habit I caught part of Tony Jones’ interview with Bill Gates on a special feature episode of ABC television’s Q and A during Gates’ fly-in-fly-out visit to Australia promoting the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. I was curious for as founder of Microsoft he doesn’t have a particularly positive image among more liberal (note the small ‘l’) thinkers. And apart from the negative press I knew little about him or the foundation. Well, I may be gullible but I was quickly impressed by his quiet manner and the way he spoke in a fairly self-deprecating style. Furthermore, my long-held sympathies towards developing nations struggling with diseases which we are hardly aware of in Australia were touched by the sincere and intelligent response from Bill Gates to a question from a Papua New Guinean Health worker. I am including a clip below if you are interested in hearing what he had to say.

Since then I have been doing a little reading about malaria and the latest reported research (across disciplines). From a simple web search one quickly sees there are a great many groups working towards reducing the incidence of malaria around the world through preventative measures such as supplying mosquito nets, removing mosquito ‘habitat’ or implementing vaccination programs, research, community development, health education, and there are also a great many people supporting through donations and fundraising. Recently, two young university students from Burkina Faso and Burundi won the Global Social Venture Competition (GSVC) for inventing a mosquito deterring soap which they named Fasoap. Quoted in an online article they said, “In our country the majority of the population lives below the poverty line… most people can’t afford to regularly buy medicines and products such as anti-mosquito creams, sprays or protective nets,” but Fasoap will be cheap enough for most households to afford to use and can replace the standard soap in the house.

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease. It begins with a bite from an infected female mosquito, which introduces the microorganisms through saliva into the circulatory system from where they travel to the liver to mature and reproduce. Symptoms of malaria may include headache and fever and can lead to coma and/or death. Unfortunately there is no vaccine yet. Resistance has already developed to several anti-malarial drugs and increasing resistance to others is becoming a problem. (Thanks to Wikipedia for some of that info). Malaria is a huge problem affecting thousands of people through ill-health as well as the loss of loved ones. The loss of economic productivity for families, communities and developing nations is also immense and an obstacle to poverty alleviation and sustainable development in many affected nations.

A novel area of research is looking at the use of insect-killing fungus such as Beauveria bassiana as an active ingredient in biopesticides (‘a form of pesticide based on micro-organisms or natural products’[i]) against mosquitoes which transmit malaria. This has become necessary as mosquitoes become increasingly resistant to existing to conventional chemical insecticides. Interestingly, research has also shown, that the slow death by biopesticides makes it harder for the mosquito to build up a resistance.

Malaria kills more than 600,000 children each year and although this seems amazingly high there is only a mortality rate of 0.3% reflecting the high number of reported cases of over 200 million. Early diagnosis and treatment significantly control the mortality rates but it has also been proven that some people (particularly from regions in Africa) are naturally able to resist greater severity of the disease suggesting genetic factors play an important role.

Current research is looking to identify the genes affecting an individual’s immunity to malaria and from this potentially understand the molecular basis of protective immunity against the disease – and be able to apply this to the development of an effective malaria vaccine. For example researchers from MalariaGEN (Malaria Genomic Epidemiology Network)[ii] are conducting four key areas of research addressing different aspects of the problem:

- Genetic determinants of resistance to malaria

- Genetic determinants of the immune response to malaria

- Human genome variation in malaria-endemic regions

- Genetic linkage studies of resistance to malaria

The following animation from the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics (Oxford, UK) which is ‘home’ to MalariaGEN cleverly explains the purpose of the research. It also has a good percussion soundtrack so turn on your audio.

This is all interesting reading for some but all of you (whoever you are) may also be wondering where smelly feet come into it or if that was just a ruse to lure you into reading my post. Well you are half right – it was designed to lure you in but it isn’t a ruse. I was inspired by the recently published research (peer-reviewed), ‘Malaria Infected Mosquitoes Express Enhanced Attraction to Human Odor’[iii], and some associated reporting[iv].

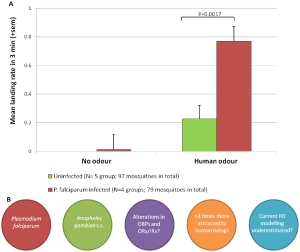

There is existing evidence some pathogens (such as malaria) can manipulate their hosts or the vector (the mosquito) to better aid in their spread from their mosquito host to assist transmission. The researchers, Smallegange et al (2013), have found mosquitoes are more likely to be attracted to human odour than others and malaria-carrying female mosquitoes (Anopheles gambiae sensu strict) are even more attracted to the human odour than those that are not infected. This is better illustrated by the useful little graph below sourced from the published paper.

Attraction of malaria infected mosquitoes to human odor. http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0063602

To cut a long story short Smallegange et al discovered this by using a nylon matrix which had been treated with human odour and a clean control nylon matrix placed in a cage olfactometer with 20 infected mosquitoes and proceeded to count how many times and beneath which nylon matrix the mosquitoes landed (including ‘probing attempts’) in a 3 minute period. The same test was separately undertaken with uninfected mosquitoes.

[As an aside, I can imagine you wondering what a ‘nylon matrix’ is – some wondrous piece of technologically advanced lab equipment? Perhaps some sort of synthetic (nylon) net (matrix)? As it turns out what they used was simply a ‘panty-sock’ – which I take to mean some version of pantyhose. And they acquired the human odour by availing a man to wear the said panty-sock for twenty hours prior to the experiment. For those who may have any concerns for the man providing foot odour, the lead researcher/author also ‘performed odour collection on herself by wearing nylon stockings’. (!?!?)]

The results show infected female mosquitoes are more attracted to human odour than non-infected mosquitoes, indicating the pathogen effects the mosquito host’s behaviour and most likely in within their olfactory system. There is further research to be done to determine what impact the lifecycle stage has on the host’s attraction to human odour, as well as odour from multiple human subjects.

Why is this important in the fight against malaria? The researchers point out, ‘Further studies on the identification of new attractants for improved mosquito surveillance or trapping programs specifically targeting P. falciparum infected An. gambiae s.s. [malaria carrying mosquitoes] females may provide powerful tools for the global agenda of malaria eradication’(p.3). Furthermore, “Every time we identify a new part of how the malaria mosquito interacts with us, we’re one step closer to controlling it better.” Dr James Logan, who headed part of the research at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine was quoted as saying in the news.com.au online article.

So in summary, we need more people to people to start using Fasoap on their smelly feet … while also spreading insect-killing fungi about. Interestingly while the fungal infection from the biopesticide can take up to two weeks to kill the host mosquito, during that time it significantly impairs the hosts ability to respond to host-related odour cues by flying up wind as well as a ‘suppression of olfactory receptor neurons tuned to 1-octen-3-ol, a mammalian odorant known to attract biting flies, including mosquitoes’[v]. It all comes back to the smell doesn’t it? And there was I believing the malaria mosquitoes were the kamikaze-esque villains but really they’re more akin to mindless zombies driven by their ‘noses’ ….. hmmm, now why didn’t I use that for a title?

So, malaria is and will continue to be fought on many fronts. While I have looked at some of the more scientific approaches, it is also clear from the extra reading I have done that an interdisciplinary approach is still required with collaboration with government and aid agencies. There is more to write in follow-up but I am now at the end of my word limit.

Take care,

the Domestic Scientist.

[i] <http://ec.europa.eu/environment/integration/research/newsalert/pdf/134na5.pdf> European Commission (2008) Encouraging innovation in biopesticide development.

[ii] ‘community of researchers in more than 20 countries who are working together to understand how genome variation in human, Plasmodium and Anopheles populations affects the biology and epidemiology of malaria, and to use this knowledge to develop improved tools for controlling malaria’ http://www.malariagen.net/about

[iii] Smallegange R, van Gemert G-J, van de Vegte-Bolmer M, Gezan S, Takken W, Sauerwein RW & Logan, JG 2013, ‘Malaria Infected Mosquitoes Express Enhanced Attraction to Human Odor’, PLoS ONE, vol.8, no.5.

[iv] ‘Stinky feet may lead to better malaria traps, help fight the mosquito-borne disease’ June 04, 2013.

Read more: http://www.news.com.au/technology/sci-tech/stinky-feet-may-lead-to-better-malaria-traps-help-fight-the-mosquito-borne-disease/story-fn5fsgyc-1226657371727#ixzz2Z1lnnpW5

[v] George J, Jenkins NE, Blanford S, Thomas MB, Baker TC, 2013, ‘Malaria Mosquitoes Attracted by Fatal Fungus’, PLoS ONE vol. 8, no.5, p.1.

With a grain of salt (or GMO corn) ….

Posted: July 13, 2013 Filed under: Day to Day Science, Health, Uncategorized | Tags: food industry, food security, genetic modification, global food system, Michael Pollan, proceessed food, science communication, science literacy, Scientific method, the Omnivore's Dilemma Leave a commentThanks to James Byrne’s (RiAus) discussion yesterday of his blogging regarding use of antibiotics in the US meat and livestock industry, I have been prompted to discuss the bestselling book, The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals (Penguin Press, New York, 2006) by US celebrity food writer and Professor of Science and Environmental Journalism at the Berkeley Graduate School of Jornalism, Michael Pollan. You may have come across the book if you consider yourself a ‘foodie’, organic agriculture supporter, agro-scientist, sustainability student, or government/big business conspiracy-theorist. I think it is also quite pertinent to the subject matter of this blog – negotiating science literacy through the intersection of science, domestic life and cultural ‘norms’.

The reason I want to talk about this work is because I read and reviewed it while undertaking another course and looked at it from the perspective of global food systems (I will attempt to post and link to my book review later). However, after a talk from Dr Paul Willis at RiAUS yesterday morning about science literacy and science equity, I went back to my original book review and realised I hadn’t addressed or even clearly acknowledged the strong science theme running through it. In fact I ignored it almost entirely. As per usual my interest was focussed more squarely upon the cultural dynamics at play. But upon reflection, Pollan comments a great deal upon science, both directly and indirectly to frame his debate on the politics of food. These comments are usually in the context of highlighting evidence and mainly about the ‘evil’ of science (muwha-ha-ha) or rather the evil of the industrial food system which has been driven forward based upon scientific breakthroughs. It does this, however, in a very dramatically engaging and entertaining style – incessantly firing selective scientific facts and figures at the reader to shock and awe. It is through the ‘unbelievable-ness’ that one believes what is claimed on the page. What does that say about how our brains process information?

The Omnivore’s Dilemma is a borrowed phrase from research psychologist Paul Rozin (1976) referring to how people’s biological ability to ingest just about anything nature offers creates anxiety when it comes to deciding what we should eat. Being generalist eaters has advantages and disadvantages, allowing us to sustain ourselves across different environments but it also means we can be faced with too much choice. Our cultural traditions which codify, ‘the rules of wise eating in an elaborate structure of taboos, rituals, recipes, manners, and culinary traditions’ (2006, p.4) are no longer reliable guides as our food chain becomes longer and more anonymous through an industrialised process.

Contributing to the omnivore’s dilemma is a modern food industry offering us cheaper variety than ever before in ever diverging processed food forms. This complicates our ability to identify what is ‘good’ food and what is ‘bad’ when contemplating health, ethical and moral questions. If eating represents our fundamental engagement with the natural world as suggested by Pollan, then our consumption of highly processed food pumped out of the industrial food chain is a rather dysfunctional and unhealthy relationship.

Pollan directs particular criticism towards the growth of the commercial GMO agriculture sector and the industrialised livestock model including the use antibiotics to enable ruminants to digest corn (because it is cheap and produces high-yielding harvests thanks to genetic modification) which hardly sounds like scintillating reading. He is, however, an undeniably great storyteller but he has also been accused of failing to tell the full story and reliably represent the science-based facts he uses. Adam Merberg[i] who is well-known online for critiquing Michael Pollan provided an opinion piece for the Berkeley Science Review which criticizes Pollan’s work for a lack of accuracy in representing the historical scientific record and failing to understand the scientific method. There is also a good discussion to found in the article’s attached comments from readers.

I guess there is a dilemma about a literary genre which is not aimed at science professionals but at the public and to be successful it therefore needs to be entertaining and compelling; hence the drama underpinned by a selective interpretation of history. I have no doubt Pollan believes passionately in what he says as do many of his readers who are likely to take a dim view of scientific endeavour after reading The Omnivore’s Dilemma as it fails to sufficiently differentiate the underlying science from what the science was used for (which is also up for debate). Pollan is criticising scientific reductionism suggesting throughout his book society is sometimes too quick to employ new discoveries without fully understanding them. This is a point I am inclined to agree with to some degree. Does this suggest there are limitations to the scientific method? Perhaps – with our somewhat fallible decision-making. I look forward to your opinions in response to that particular query.

Pollan is a very successful and plausible communicator who knows his audience. Whether or not you agree with his opinions, his work is bringing application of science up for debate by popular audience through demonstrating its significant place in their lives; albeit not always in a good light. But isn’t this important too? I don’t think anyone would suggest it is good for science should be isolated from challenge. And all too often, science is presented as fact while failing to provide contextual meaning for society as a whole. I believe science communicators need to take this into account, recognise that this (science communication) is contested territory and attempt to better understand how science is (and can be) accessible and meaningful to the populace. It seems to me (as a non-scientist) this is particularly hard for scientists to appreciate properly without understanding what fundamentally motivates people is not always black and white.

I leave you with the loaded question, how do authors like Pollan contribute to or detract from science literacy and/or equity? Happy reading.

from the domestic scientist

[i] At the time of writing the article in 2011, Adam Merberg was a Ph.D candidate in Mathematics at UC Berkeley.

Science art | Royal Society Summer Science Exhibition 2013

Posted: July 11, 2013 Filed under: Science & Art 2 CommentsScience art | Royal Society Summer Science Exhibition 2013.

What could be better? Using art to communicate Science. I think these works are painting on silk by artist Odra Noal. Perhaps a new range in soft furnishings?